I see a lot of

writers – mostly newer ones, I suspect – propagating various myths about

writing and publishing on social media. When I first started going to science

fiction conventions in my late twenties (back in Bedrock with my good pals Fred

and Barney), my friends and I would huddle between panels and talk about

writing “secrets” and insider info we’d heard from panelists and other

con-goers or read in how-to-write books and publications like Locus. There

was no Internet back then or social media, but we still managed to find plenty

of mistaken beliefs to discuss and adopt as best practices or professional

standards, until eventually we gained enough experience to know better. I can’t

begin to imagine how difficult it is for writers starting out today to sift

through all the advice they read online or watch in YouTube videos and separate

the wheat from the chaff. And it doesn’t help that some writing/publishing

myths have a grain of truth in them, although perhaps not where you’d expect,

or that some myths are both true and not true, depending on how you look at

them. Following is list of writing/publishing myths – or perhaps beliefs

might be a better word – presented in no particular order, along with my take

on them.

· You must

outline/not outline. This

is the Plotter vs Pantser debate, and people get so passionate about which side

they think is best that I often expect them to go to war over the issue. I

swear, it’s like a damn religion for some people! Neither approach is better or

worse than the other. If one works for you, great, but that doesn’t mean it

will work for others, and you shouldn’t try to force people to adopt your

preferred technique or chide them when they don’t. It’s also okay to do a

combination of each or to change from one to the other for different projects.

I tend to outline novels but then pants scenes when I develop them. I outline

short fiction a bit but usually pants it. I outline instructional nonfiction

(like this blog entry), but I don’t outline personal essays. I have no idea why

these different techniques work for me in different situations, and I don’t

really care. It’s enough for me that they do. But if for some reason pantsing a

short story isn’t working for me, I’ll try outlining. Writing techniques are

tools and we need to use whatever tools work best for the job we’re attempting

to do.

· You must write

many drafts/write only one draft, etc. I saw someone post about this on Twitter

the other day. She said that writers must write at least five drafts of a

novel. Of course, some people agreed with her, some didn’t. The problem with so

many writing/publishing myths is that inexperienced (or non-introspective)

writers assume their experience is universal and applies to all writers. Hell,

it won’t even apply to themselves consistently throughout their career. I work

out ideas, plot threads, scenes, dialogue in my head before I sit down to

write, and I edit as I go. By the time I finish a draft, it may need a little

polishing, but I don’t do a significant rewrite. Other people are discovery

writers, and they may need to produce any number of drafts to find out what

they’re trying to say and exactly how they want to say it.

· You’re only a real

writer when . . . There’s

no such thing as a “real” writer. All writers are real. (Some of us are even

surreal!) I think “real writer” is shorthand for “What knowledge/practices/accomplishments

are necessary for someone to be considered a professional writer?” People want

clear, specific standards that will help them measure their career progress. The

problem is that there aren’t such standards in the arts. There are specific

steps to follow to enter most careers, but there are none in the arts. People

create their individual paths. They can get ideas on how to forge those paths

from established artists, but they can never replicate the exact steps another

writer took to find success. Comparing ourselves to others can be a good way to

learn what to try and what to avoid, but we must be careful not to allow such

comparisons to impact how we view ourselves. The “real writer” myth is one that

can quickly become poisonous.

· You need to be on social

media – all of them. You

don’t need to do a damn thing in the arts unless you want to, including

producing art in the first place. Social media can help you network, find out

about markets, learn what different artists do, what works for them and what

doesn’t, see professional (or unprofessional) behavior modeled, follow agents

and editors to learn what they’re currently looking for, etc. It can also help

you find fellow artists to connect with so you can develop a support network

and (hopefully) not feel so alone as you work on your art and career. Yes,

social media can help you reach an audience who will buy your work, but I’d

argue the other benefits I mentioned are more important and will probably give

you a better ROI on the time you devote to social media. I’ve read a number of

articles that suggest three social media platforms is about the most a person

can keep up with comfortably, and I’ve found that’s true for me. If you only

like one social media platform and find it fulfilling, that’s fine, and if you

hate social media, to hell with it.

· Self-pub/trad-pub

is best. Neither

is best. They’re just different. Self-pub gives you more overall control of

your work and its marketing, but it takes a lot more time and effort, as well

as initial investment of money on your part (for developmental editing, cover

design, copy-editing, etc.). A traditional publisher will provide most of those

services, but you may have to make compromises in terms of your story or its

presentation to the public. I think writers should try all venues at first –

self-pub, traditional publishing (both large press and small press) and see

what works best for them. You’ll also increase your odds of success this way.

Maybe you never considered self-publishing, but you try it and that’s where you

find your readership. But arguing which one type of publishing is better overall

is ridiculous and pointless.

· You must have beta

readers or a critique group. I think by now you get the idea that I

don’t believe in musts. I do think that there are some techniques that are

important and most writers will grow as artists and attain some level of

success faster by employing them. Beta readers are one of these things. Whether

you take a creative writing class or form a writers’ group (face-to-face or

virtual), giving feedback on others’ writing and getting feedback on your own

work is probably the single best way to learn. Getting feedback from a professional

is best, but most professionals are too busy writing their own stuff to do

in-depth feedback for others. Some writers find beta readers invaluable and

continue using them throughout their career. Others (maybe most) use beta

readers in the early stages of their career when they’re still learning, and

when they start publishing regularly, they stop using beta readers. I last

belonged to a writers’ group over twenty years ago. I reached a point where I

was selling work regularly and had deadlines, and sometimes I had to submit

stories before my group could get to them, especially when it came to novels.

Plus, I write fast and write a lot, more than a group can comfortably keep up

with. AND my group – although it included science fiction and fantasy writers –

thought a lot of my fiction was too weird and should be made more ordinary, for

lack of a better word. As a working professional, I have an agent and editors

at the various publishing houses I work with. Those are all the readers I need

now. But there isn’t a damn thing wrong with being part of a writers’ group

forever, being part of a group at some times in your career and not others, or

seeking out feedback only when you feel like you really need it.

· You should never

listen to feedback because it will change your natural style and rob your work

of originality. On

some level, I guess this is one of the things I said about my former writers’

group when it came to their response to my weird-ass horror fiction. But I

didn’t choose not to use their feedback from ego or laziness. I’d been getting

feedback from teachers, friends, and writing groups for over a decade by that

point, and I did my best to learn from it and make my stories better. I

eventually began selling weird-ass horror short stories, and editors and

readers were responding quite favorably to them. I figured that was a good sign

that I should plow ahead with that style and see how far it could take me. It

hasn’t gotten me a huge readership, but I’m happy with the work I’ve produced

and that’s what’s important to me. One of the criticisms of the workshop method

of teaching creative writing is that eventually all the students’ work sounds

the same because they end up creating fiction that appeals to a group with

different tastes, and in order to please everyone, they have to make their work

as generic and bland as needed to gain the group’s approval. Getting and using

feedback is a balancing act. You don’t want to be so resistant to it that you

refuse to consider it, but you don’t want to wholeheartedly adopt every

suggestion, either.

· You need a degree

in creative writing, preferably an MFA to be a real writer. Nope. Most writers

I know don’t have a degree in English if they have any degree at all. If you

want to be a writer you need to read a lot, write a lot, get feedback on your

work, and keep trying to improve – and you do all this until you die. Now how

you go about doing these things, especially during your early

learning/preparation stage is up to you. If you feel like a structured

experience guided by professional writers and working alongside like-minded peers

would be a wonderful way to grow as a writer, go for a degree. If you

can afford it, and if you can devote the time necessary. I graduated

with an MA in Literature with a Creative Writing Concentration in 1989. I

didn’t fully understand the difference between an MA and an MFA or I would’ve

gotten the latter degree. I got my MA because I wanted guided instruction in

Literature with a capital L as opposed to just reading it on my own, and

because with a graduate degree in English, I knew I could teach college

composition courses part time while I wrote. Eventually, I realized I loved

teaching so much I sought a full-time gig and was fortunate enough to land one

(plus, I had two young daughters, so I needed to make more money and have good

health insurance.) Some writers think an MFA will give them some kind of

official status as a Real Writer, but it doesn’t. I know a number of people

with MFAs who haven’t written a word since graduating, as well as people who

struggle to get published as much as they did before they got their degree.

There is so much information on how to write available freely available on the

Internet, so many instructional videos on YouTube, so many writers talking

about their lives, work, and process on social media, that you can teach

yourself as much, if not more, than you could learn from an MFA program in

terms of sheer information. It’s the experience of being with good teachers,

strong peers, and having time to focus on your writing that you can’t replicate

on your own (not easily, anyway). Still, in the end, you don’t need no stinkin’

degree to be a writer.

· You need to write what

sells/you need to write art for art’s sake. This is where the Satanic

Commandment comes in: “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law.”

Whatever goals you have for your writing are good goals. Some people want to

focus solely on the art and craft, others want to focus on making money from

their work, and others try to find some kind of middle ground between the two.

Going into the arts is a terrible way to make a steady income, but it’s a

fantastic way of feeding your soul and giving your life meaning. All writers

want the dream of being able to produce whatever kind of work we want, having

critics laud it for its brilliance, having millions of readers adore it, and

have trucks full of money pull up to their houses hourly. The truth is that

only a small fraction of the human race reads for enjoyment, and if you write

weird-ass horror like me, only a very small fraction of the human race will

read it. It’s hard to make a living – even an extremely modest one – from

writing fiction alone. Evidently writing weird-ass horror is more important to

me than money or else I’d write in a more popular genre, like thrillers (but

even writing in a popular genre doesn’t guarantee monetary success). My day job

gives me and my family the money and benefits we need, plus it feeds another

part of my soul – and it still focuses on writing. My goal has always been to

create a life in writing, and in that I’ve succeeded. (I’ll still take all the

money the world is willing to throw at me, though. I’m not stupid.) So write

for your own reasons, and those reasons can change from project to project as

well as throughout your life as your needs and wants change. It’s all good.

· You shouldn’t

write about people different from you; you should write about people different

than you. I

don’t think of this as a myth so much as an artistic and ethical issue. Some

writers (often younger ones) say you shouldn’t write about anyone unlike

yourself in significant ways. As I said early, I’m a straight, white, cishet

male, and I’m fifty-nine and have lived in America all my life, most of it in

Ohio. I have diabetes, but my overall health is fine otherwise. If I try to

write from the perspective of a blind nonbinary teenager from Tanzania, no

amount of research will help me portray this character in a truly authentic

way. Plus I could unknowingly perpetuate harmful stereotypes. Also, if an

editor buys a book about this character from me, that will potentially take a

publishing slot away from a writer whose life experience more closely matches

that character. On the other hand, if we only write about characters like

ourselves, we’re writing autobiography for the most part. Plus, I’ve had people

of color tell me that if writers only include people exactly like themselves in

their stories, they’re erasing everyone else from the world of the story. So by

not including characters different from ourselves in terms of age, race, sexual

identity, gender identity, place of origin, we fail to depict the world as it

is and lose the opportunity to help readers develop empathy for people who, on

the surface at least, don’t appear to be like them. So what should we do? We

should do what we feel creatively impelled to do. If we want to write about

someone very different than ourselves, we should ask why we want to do this and

why are we the best person to tell this story? Is there someone else who could

tell it better? I’m perfectly comfortable writing about young people because I

interact with them all the time at my college. But while I would put a younger

character into a horror novel, I wouldn’t write a novel about what it’s truly

like and what it means to be a younger person in America today. You’ll need to

make your own decisions on how to handle writing diverse characters, but try to

do so thoughtfully and respectfully.

· You must pick a

specialty and stick to it. In other words, brand, baby, brand! Living in a

capitalistic society, we’re urged to make everything – including ourselves – an

easily identifiable, simple product. We are what we do, we are our labels. It’s

true that branding yourself as a sweet romance writer or a military science

fiction writer can make it clear to readers what kind of experience your

fiction offers and will help you connect with a specific audience. That’s

capitalistic thinking, but it’s also artistic thinking. As an artist, we want

to find people with whom our work resonates. But doing the same thing over and

over again can get tedious for artists. So if you want to write different kinds

of stories whenever you feel like it instead of producing one hardboiled

mystery novel after another, do it. But if you love a certain kind of fiction

and you’d love to toil in that field for the rest of your life, do that.

· You should write

every day. I

get interviewed a lot, and I’m almost always asked if I write every day. Once a

project gets going, I tend to work at it steadily until it’s finished, so I do

write every day then. But sometimes I enter fallow periods where I don’t write

much, or at all. I may write story notes, play with ideas, maybe write a rough

outline as I search for a new project to work on. Sometimes I know exactly what

I want to write but getting started is hard. Sometimes my life circumstances

aren’t conducive to writing every day. It’s true that the more often you write,

the more skilled you become, and the more publishable work you will produce

over time. Making writing a regular practice is important. But if you hit a

period where you don’t write every day, you’re not a failure as a writer. Just

do your best to get back to it when you can.

· You don’t need to

be a reader to be a writer. I don’t get this attitude, but it’s not an

uncommon one, especially among younger people who spend all their time

consuming visual media and playing video games. I think what most of them would

like is to write scripts for movies or create videogame scenarios, but it’s

easier to sit down at a computer, open Word, and just start typing. Maybe they

feel the odds of success in movies or videogames are so slim that they’ll

settle for writing fiction. Can you write fiction without reading much if at

all? Sure. Will it be any good? Probably not. But who knows? Maybe you’re the

one genius in billions of humans who can produce great art without having had

much experience with the art form as audience member. If so, go with god. Most

writers I know grew up as voracious readers and remain so. (I’m so busy all the

time these days that I don’t get to read much myself. I tend to listen to

audiobooks as I drive.) To me, not liking to read and wanting to be a writer is

like not enjoying eating but wanting to be a chef.

· You must read the

classics to be a writer. Read whatever you damn well want. Whatever makes you

happy, whatever inspires you, whatever teaches you how to be a better writer.

Every genre has its classics, though, and it’s not a bad idea to at least

sample them to get a feeling for what’s come before, plus you might find

inspiration in classics, maybe updating their themes and narrative approaches

for a new generation. But must read them? Nope, nope, nope. Reading

contemporary fiction – the kind editors are buying and readers are currently

reading – is arguably more important.

· You must write

fast/you must take your time. Releasing shorter books more often is a

marketing tactic for indie writers, so if you can write fast, that can be a

benefit for you. Taking your time, though, means that you can continue to

improve a piece of writing until you believe it’s the absolute best it can be

before you send it out into the world. But whether you write fast, slow, or in

between, it doesn’t matter. All that matters is the quality of the final work. And

your speed may change from one project to another. If you are a slow writer,

don’t take on projects with definite deadlines that you may be likely to miss.

If you’re a fast writer, don’t give into the temptation to abandon a project

the instant it’s finished and move on to another. Spend at least some time revising

and improving your work before publishing it.

· Writing awards are

important; writing awards are meaningless. Winning an award for your writing

means that your peers recognize that you’re doing good work. It doesn’t,

however, mean no one else is doing good work. It just means that one

particular group at one particular time chose to honor one particular writer

(you). Some writers hate the entire concept of writing awards, seeing them as

inspiring unnecessary competition among writers and motivating them to focus on

awards as the sole purpose of writing – and then feeling like shit and thinking

they’re a failure when they don’t win. Or if they do win, they’re tempted to

believe they’ve Made It and might end up resting on their laurels instead of continuing

to grow as artists. And since writing awards are subjective, people are always

going to argue about them. But that’s good (even if it sometimes makes people’s

emotions run high). Discussing what makes good writing broadens people’s ideas

about writing overall. Although some people are bewildered – and a few become

apoplectic – that the work they view as superior wasn’t nominated for an award,

let alone won. Awards are given (ideally) to promote writing in general as

much, if not more, than to honor individual writers. Once a year, the news goes

out that a group – like SFWA, HWA, MWA, WWA, etc. – has presented their awards,

and people are reminded that yes, science fiction, fantasy, horror, mystery,

westerns, romance, literary fiction, poetry exists, and they’re given a list of

writers they can check out, many of whom may be new to them. Winning an award

also gives writers another way to promote themselves. I’m Multiple Bram Stoker

Award-Winning Author Tim Waggoner. But does this actually help your career?

Like so much when it comes to promotion, no one really knows. But it can be an

additional weapon in your promotional arsenal. Bottom line: literary awards can

be a very mixed bag, but you shouldn’t allow them to distract you from your

work or fall into the trap of believing your self-worth is tied to them

somehow.

· You must spend a

ton of time promoting your work. Traditionally published writers would love

to believe that publishers will do all the promotion of your work, leaving you

to get on with writing. Publishers will promote your work to a certain degree,

but they won’t do a ton of promotion. In general, small-press publishers will

work harder than larger publishers for their authors, but they only have so

much money to spend on promotion. Larger publishers have more money, but they

generally wait for a writer to sell well before putting a lot of effort

into promoting them. They treat the first few novels an author puts out like a

lottery. The authors who sell well get more attention and money for promotion.

It makes sense from a business standpoint. An already successful writer is a

better return on investment. Self-published authors have to do all of their own

promotion, and traditionally published authors still need to promote their work

too – if they want to. If you treat your writing as a business and you

depend on its income for your living, then you better promote the hell out of

it. But if you have a day job – as I do – you should do as much or as little promotion

as you have energy and time for. If you really hate promotion – I mean loathe

it – don’t do any. But whether or not you make our living from your writing, promotion

is how you make readers aware of your work, and if you don’t do at least some,

you leave it up to luck whether or not anyone ever finds your work. We write to

be read, so we want to get our work into the hands of readers. On the other

hand, promoting 24/7 can cause you to burn out fast (and it leaves you little

to no time to write new work). And like I said earlier, no one has a clue what

kind of promotion works, or when it does work, how to replicate that success

next time. Promotion is a gamble, but you decide how far you’re willing to go

with it.

· Real writers are

completely and totally dedicated to their writing 24/7. This is bullshit.

It’s okay to have a nonwriting job or to practice other art forms along

with writing, whether for economic or self-actualization reasons. Plus, doing

things aside from writing gives you different experiences that you can draw on

for your writing. During the COVID lockdown, I found it harder to write fiction

because I wasn’t getting enough input. I wasn’t going places, seeing things,

talking to people . . . I wasn’t getting the raw material I needed to create my

stories. Having a life outside of writing is what makes writing possible.

· There are gatekeepers/a

secret writing cabal. Nope. At least not in the way that most people

imagine. In traditional publishing, some writers’ work is accepted and some is

rejected for all kinds of reasons, some on the aesthetic side (an editor

prefers quiet horror, not the kind of extreme horror you write), some on the

business side (an editor thinks their readers will like one story more than

another, even if they’re both well written). Editors aren’t trying to keep you

out of their magazine or off their publishing roster. They’re simply trying to

find the best stories of the kind they think their readers will like. And their

choices, while informed by hopefully having read widely in their genre, are in

the end subjective. To editors, it’s not about you or your story. It’s about

fulfilling their readers’ needs. Editors, especially in the small press, do

tend to work with their friends more often than with people they don’t know.

But editors became friends with these writers by publishing their work first

and then getting to know them. And they continue publishing their

work because they like it, their readers like it, and they have a good working

relationship with these writers. Now when it comes to writers networking with

other writers, there are groups of friends and support networks that develop,

and people like helping out people they like and vibe with. That’s human

nature. It sucks when you’re not part of a particular friend group or support

network. No one likes to be on the outside looking in. Are there people –

writers, editors, publishers – who exclude others based on gender, race, gender

identity, sexuality, etc.? Of course. That kind of gatekeeping occurs, but as a

cishet white guy, I’m not a victim of it, and I’m not sure how often it

happens. I listen to others with direct experience of this sort of

discrimination and try to learn from them.

· Only writers other

than cishet white men can get published these days. On the other hand,

some disgruntled writers – white, cishet, males, naturally – complain that they

are being discriminated against in the current publishing landscape. This is

horseshit. Editors may be working on broadening the types of stories and

writers they publish, but white cishet males still dominate publishing. Some

people just get pissed when they’re asked to scoot over and make room for

others at the table.

· You must have a

literary agent; you don’t need a literary agent. If you want your

book to be traditionally published by a larger, mainstream house, then you

definitely need an agent. It’s rare that these publishers look at unagented

submissions, but some will have open reading periods that they announce on

social media, so if you don’t have – or don’t want – an agent, follow

publishers you’re interested in on social media so you’ll be sure to see such announcements.

If you want to publish books with a small press, no agent is required. Small-press

publishers will work directly with writers. And if you’re a self-publishing

writer, you don’t need a book agent. You might want one who can try to sell the

film, TV, audio, and game rights to your book, though. And if you send an agent

a query for a project, and they tell you that it doesn’t resonate with them but

they hope you’ll send them your next book, they mean it. No editor or agent

will make extra work for themselves unnecessarily, so if they ask to see your

next novel, and you’d still like to work with them, send it.

· Blurbs from other

writers are vital for promoting your books; blurbs are meaningless. Writers hate

asking other writers for promotional blurbs, and if they’re lucky, their agent

or publisher will go fishing for them. Some writers believe that it’s vital to

have endorsements from other writers to help sell their books, but the truth is

there’s no proof they actually help. A blurb from a writer a reader likes might

make them pick up a book and check it out, but it won’t make them buy it. And –

based solely on anecdotal evidence I’ve seen on social media – most readers pay

little-to-no attention to blurbs. I gather blurbs from reviews of my work and

use those instead of asking other writers for them. I frequently get asked to

do blurbs, but I often don’t have time to read the book before the blurb

deadline. I try to get to them, and I always feel awful when I can’t deliver.

So I guess my take on blurbs is they can’t hurt and they might help, so if you

want them, go get some. Don’t be afraid to ask authors for blurbs and don’t

take it personally if they say they’re too busy, or if they say they’ll try to

get to your book but don’t manage to.

· Trigger warnings

are important and necessary for readers; trigger warnings aren’t necessary and

can detract from the reading experience by acting as spoilers. Both of these statements

are true and both are false. It all depends on the reader. There are ardent

(and at times strident) advocates of both positions, and fights about which

approach is better regularly flare up on social media. Some psychologists

believe that trigger warnings don’t prevent readers from experiencing negative

reactions if they’re warned about the possibility ahead of time, and that such

warnings can be harmful by encouraging a victim mindset, potentially delaying

someone’s recovery from trauma. So I don’t put trigger warnings on my books.

Reviewers of my books sometimes include detailed trigger warnings in their

reviews, and I have no problem with that (and it’s not like I could do anything

if I did have a problem with it). And if a publisher asked me to include

trigger warnings, I’d explain how I feel about it, and if they still insisted I

include them, I probably would. But you know what I don’t do? Demonize anyone

who believes trigger warnings are vital and absolutely necessary. And if you’re

a proponent of trigger warnings, I don’t think you should demonize those who

choose not to include them with their work. If as a reader you insist on

trigger warnings, choose to read books that have them. If you dislike trigger

warnings, don’t read books that have them. And you can state what your

preference is on social media without saying anyone with the opposite view is

evil and uncaring or too fragile emotionally.

· Writer’s block is

real; writer’s block is not real. “I don’t believe in writers’ block.”

Whenever I see someone say this on social media or on a panel at a con, I think

some variation of, You might not believe that touching a poison dart frog

will kill you in seconds, but that’s only because you’ve never touched one.

Writers who scoff at the existence of writers’ block make the same mistake that

so many humans do. They think their experience is universal. It never seems to

occur to them that someone else might have a different experience. I think

writers’ block is a shorthand way of referring to any number of situations that

can interfere with a writer’s ability to regularly produce prose. Maybe you’re dealing

with health or emotional issues. Maybe your family needs you to focus on them

right now and you don’t have enough energy left over for your writing. Maybe

you’ve experienced a devastating professional setback. Maybe you had to put

down a beloved pet and you’re grieving. All of the causes are different, but

the result is the same: you’re not writing. Some of these situations will

resolve themselves with time. Some may necessitate you putting work in to overcome

them. I’m prone to depression, so I take meds and have gone through a lot of therapy

to give me tools to deal with my depression when it gets bad. Some situations

may require that you rearrange your life and try to find new ways of getting to

your writing. The most important thing is to understand that you are not blocked

from writing forever. It may not be easy, but you can get past it. I regularly

recommend the work of Eric Maisel, a therapist who helps artists deal with the

emotional challenges of being a creative person: https://ericmaisel.com/

· Agents and editors

need to understand the power they hold over writers. This is a relatively

new belief/attitude I’ve seen some writers express on social media. They rail

against editors and agents who take a while to get back to writers on submissions.

(A while being anywhere from a few weeks to a year.) “Don’t they

understand how that makes us feel?” these writers say. “It’s not fair that they

hold so much power over us!” I get how frustrating and demoralizing it can be

to wait a long time for a response from an editor or agent, and sometimes you

get ghosted and never get a response. My agent and I get ghosted by editors now

and again, and if I reach out to editors on my own, I sometimes get ghosted

too. I started writing and submitting before there was email. I remember what

it was like to check the mailbox every day, hoping there would be a response

from an editor or agent. Dealing with disappointment, frustration, and

heartbreak is normal for creatives. The current attitude of “Don’t they understand

what they’re doing to us?” seems like positioning yourself as a victim of abuse.

And if yours was the only submission an editor or agent had to consider, a long

wait time for a response would be unprofessional. But you’re competing

with hundreds of submissions that agents and editors regularly receive. And

agents and editors need to tend to authors they already work with too. And of course

they’re human beings with lives that can impact their response times. If you

hate waiting for responses, self-publish. Then you’ll have total control and

won’t have to wait for anyone. That’s one of the main benefits of

self-publishing. It seems to me that many people today believe the greatest

evil they can experience is feeling bad, and if they do feel bad, someone must

be responsible, and that someone needs to be brought to justice (even if their

punishment is only getting called out on social media). People do experience

serious abuse, or course, but I’m not talking about that. I’m talking about

smaller, everyday emotional difficulties and frustrations, like getting to the

pharmacy three minutes after it closes or being stood up for a date. These

things suck, no doubt, but they don’t come close to the seriousness of actual

abuse. These writers always bristle if someone advises them to develop a thick

skin, but that’s the most useful thing they can do in this business. And if you

do experience super-long wait times or truly unprofessional behavior from an

agent or editor (such as sexual harassment), spread the word far and wide,

whether you do so publicly or within your writing network.

This entry turned

out to longer than I expected it to, and if you made it here to the end, I commend

you on your fortitude. I suppose the biggest takeaways from this entry are to

not believe in Musts in the writing world, and to remember that one size

doesn’t fit all. Someone else’s experience of writing and publishing might be

different than yours and vice versa. And don’t immediately accept any writing and

publishing advice you come across without checking to see what others think and

comparing it to your own experience. And that includes my advice too.

Gather all the

information about writing and publishing that you can, but think for yourself

and make the choices that seem best for you.

·

BONUS MYTH! Writers must attend in-person conventions

to make the right connections/in-person conventions aren’t important for your

career. Thanks

to writer Eva V. Roslin – https://roslineva.wordpress.com/

– for suggesting I add this one! The short answer is that both statements are

true (except for the “must”). Writing conferences – especially larger ones like

Stokercon, World Fantasy, Worldcon, Thrillerfest, Buchercon, Romance Writers of

America Annual Conference, the Association of Writers and Writing Programs Annual

Conference, the Society of Children's Book Writers and Illustrators Summer and

Winter Conferences, and the Western Writers of America Annual Conference – can be

excellent places to meet and schmooze with editors, agents, and other writers.

If you’re a newer writer, there are numerous panels, programs, and workshops

put on by established pros for you to learn from. Hell, you can be an old vet

like me and still learn a lot. I like going to panels about new developments in

the field, current publishing trends, and areas of writing I don’t specialize

in, such as screenwriting or poetry writing. Scheduled programs are also a

great way to find people that might be hard to track down otherwise, and you

can try to speak to them after the panel or, now that you know what they look

like, approach them elsewhere at the con to talk. There are often scheduled

pitch sessions with editors and agents, and if you manage to snag one (always

sign up as early as you can!), it can be a serious boost to your career. Meeting

writers and making connections with them can help you develop a support network

as well as lifelong friendships. Connecting with people face to face can make a

big difference business-wise. People prefer to work with people they like, and

you can get a deeper sense of who someone is and whether or not you vibe with

them during a ten-minute conversation that you might be able to in ten months

of seeing their social media posts. But do you need to go to

conventions? No. Back before websites, social media, and Zoom, a lot of

publishing business was done at cons because you couldn’t easily connect anywhere

else. (Back then, the belief/myth was that you needed to live in New York in

order to network with agents, editors, and publishers.) But as different types

of communication tech came along, more people started using it and fewer people

traveled to conventions. The World Fantasy Convention – a professionals-only

con with no fans – used to be the place to do business in SF/F/H. Everyone

in the field attended. It’s become increasingly smaller over the years, and now

it’s hard to do any significant networking or business there. I think it’s a

lot easier to network with small-press publishers and editors at cons. You can

usually find them in the dealer’s room at their bookselling table, and you can introduce

yourself, chat with them, and pitch your book. There are a number of downsides

to attending in-person cons, though. Time and money are perhaps the biggest

issues. Not everyone can get time off from their day job to attend cons, and

not everyone can afford to pay for travel, a hotel room, and meals. Even if you

try to do everything the cheapest way you can and try to share costs with

friends, it can still be a lot. I’m privileged to have the job I have.

Attending writing conferences goes hand-in-hand with teaching creative writing,

so if I need to take a day or two off from teaching, it’s not a problem, and if

my department has travel funds available, I can ask for some. The money may not

pay for everything, but it sure helps. Another issue is access. Not everyone is

physically able to do in-person cons, and if you do go, you may find that the “accessible”

hotel isn’t really accessible to people with different mobility needs. And if

you’re an introvert (as most writers are) trying to network for four days straight

can be exhausting, if you can bring yourself to do it at all. I tend to be

quite shy, and I often can’t bring myself to join in conversations at cons,

even if I know the people talking. Hanging out at the con bar and staying up

late talking is an excellent way to network with other night owls – if you can

do it. I used to be able to do it fine in my younger days, but it’s harder for

me now that I’m older. I don’t know why. After the advent of COVID, a lot of

cons switched to virtual events, and many are continuing to offer at least some

of their programming as virtual components for people who can’t physically

attend. I hope this trend continues and expands until entire conferences are

available virtually to everyone, everywhere. For decades, writing conferences

have been a primarily attended by white middle-class people, and having a

robust virtual option – at a reduced rate since those virtual attendees don’t

have access to certain on-site activities and facilities – will go a long way

to making cons more equitable. Writers can also use cons to feel like a

professional writer and be connected to the publishing community without doing

much, if any, actual writing. There’s nothing wrong with networking via social

media and sending work to agents and editors via email or Submittable. The

writing is always what matters the most. And once you start working with

editors regularly, you can skip the slush pile. I’ve done a lot of business at

cons over the decades I’ve attended them. I first connected with Marty

Greenburg at a World Fantasy con, and I placed dozens of short stories in

anthologies he published. I pitched my first Leisure novel, Like Death,

to Don D’Auria at a World Horror Convention, and I’ve followed him to Samhain

Publishing and now Flame Tree Press. All told, I’ve published eleven books with

him. I’ve made a number of tie-in deals at cons, and I’ve successfully pitched

projects to editors at cons – including Writing in the Dark. Could I

have gotten all those deals without attending face-to-face cons? Maybe. But my guess

is probably not. At cons, I learned how to approach specific editors from other

writers who shared info in person that they wouldn’t put in writing, and that

was a huge help. But even though I’ve published over fifty novels and won

awards, that doesn’t mean every deal I try to make at a con comes through. I’ve

had lots of conversations over the years with editors about projects that never

came to fruition (at least with them), and some editors will ask me to submit a

manuscript and a proposal and it sits on their desk (or more accurately, in

their email inbox) for months, if not years before I hear anything – if I ever

get a reply. I have no idea how much of a “name” I have in the horror field,

but it hasn’t seemed to make networking at cons much easier. I do get asked to

submit to some anthologies, but not others – even when they’re edited by people

I know – and sometimes when I learn of an invite-only anthology’s existence and

ask an editor if I can submit, they say they’ll be sure to let me know when

submissions are open, and the next thing I know, the table of contents are

announced, and I never heard anything. I don’t mean any of this to sounds like

sour grapes. I write and publish plenty of material regularly and have no call

to complain. I mention it to show that even being an established professional

and attending cons regularly doesn’t necessarily equate to success. And one

more thing about cons – it can take a few years of going to them and networking

before you see any professional benefit. It helps if you become part of the

community (or a community) that attends these cons, and that can take

some time. This is the closest thing to a secret cabal of gatekeeping writers

that some people talk about. Going to cons can help your career if you can

network successfully at them and you’re willing to wait to see any significant

results. But they can be expensive, access can be a problem, and just because

you do network with people, publishing success is by no means guaranteed. If

you’ve never been to a big con before, and if you have the means and ability,

try one out and see if you like it. If you do, but can’t afford to go every

year, go every few years. But like so much of the advice I’ve offered in this

blog entry, in the end, you should do what works best for you.

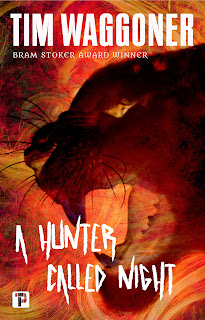

DEPARTMENT OF

SHAMELESS SELF-PROMOTION

A

Hunter Called Night Out Soon

My next horror

novel for Flame Tree Press, A Hunter Called Night, will be out May 9,

2023. Advanced reviews have been good! My favorite so far is from Jess at

Goodreads: “If Quentin Tarantino dropped some acid and then got into an Uber

with Guillermo del Toro, who just ate a handful of magic mushrooms, and they

rode to Studio Ghibli and stumbled into Hayao Miyazaki’s office for a

brainstorming session, not even they could come up with anything remotely near

this book. Holy shit.”

Synopsis:

A sinister

being called Night and her panther-like Harriers stalk their quarry, a man

known only as Arron. Arron seeks refuge within an office building, a place

Night cannot go, for it’s part of the civilized world, and she’s a creature of

the Wild. To flush Arron out, she creates Blight, a reality-warping field that

slowly transforms the building and its occupants in horrible and deadly ways.

But unknown to Night, while she waits for the Blight to do its work, a group of

survivors from a previous attempt to capture Arron are coming for her. The

hunter is now the hunted.

Order Links

Flame Tree: https://www.flametreepublishing.com/a-hunter-called-night-isbn-9781787586345.html

Amazon

Paperback: https://www.amazon.com/Hunter-Called-Night-Tim-Waggoner/dp/1787586316/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=1668832377&sr=1-1

Barnes and

Noble Paperback: https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/a-hunter-called-night-tim-waggoner/1142487192?ean=9781787586314

NOOK: https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/a-hunter-called-night-tim-waggoner/1142487192?ean=9781787586352

New

Audiobook Released: Love, Death, and Madness

Three of my

award-nominated novellas of horror fiction are now available as one audiobook

from Crossroad Press. They’re narrated by Gary Noon, who’s done a fabulous job

bringing to life a number of my previous audiobooks.

The

Winter Box

Winner

of the 2017 Bram Stoker Award for Superior Achievement in Long Fiction

It’s Todd and

Heather’s 21st anniversary. A blizzard rages outside their home, but it’s far

colder inside. Their marriage is falling apart, the love they once shared gone,

in its place only bitter resentment. As the night wears on, strange things start

to happen in their house—bad things. If they can work together, they might find

a way to survive until morning...but only if they don’t open the Winter Box.

A

Kiss of Thrones

Finalist

for the 2018 Bram Stoker Award for Superior Achievement in Long Fiction

Lonny lost his

beloved sister Delia thirty years ago. Since then, he’s sacrificed many lives

in order to return her to the world of the living, but without success. His

next target is Julia, a young women with a unfulfilled marriage and a passion

for ’80s horror films. She will soon discover that not only is real life more

complicated than the movies, it’s far more terrifying.

The

Men Upstairs

Finalist

for the 2012 Shirley Jackson Award for Best Novella

He finds her

crying in the lobby of a movie theater and takes her home to his apartment, a

strange, beautiful woman with no last name, a mysterious past, and a powerful

sexual allure. He wants her, and she wants him. There's only one problem: the

Men Upstairs. She used to belong to them—and they'll do anything to get her

back.

Order Link:

Scheduled

Appearances

Stokercon. Pittsburgh, June 15-18. I’ll be conducting a workshop

called The Horror Hero’s Journey, which is about how to apply the hero’s

journey template to horror fiction. Sign-up information for the workshop isn’t

available yet, but I’ll be sure to let you know when it is. In the meantime,

here’s the link for the convention webpage:

https://www.stokercon2023.com/

Where

to Find Me Online

Want to follow

me on social media? Here’s where you can find me:

Website: www.timwaggoner.com

Twitter:

@timwaggoner

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/tim.waggoner.9

Instagram:

tim.waggoner.scribe

Blog: http://writinginthedarktw.blogspot.com/

YouTube Channel: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCZEz6_ALPrV3tdC0V3peKNw

No comments:

Post a Comment