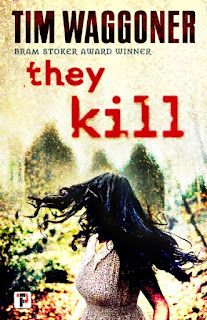

My novel They Kill, my

second release from Flame Tree Books, is now out. Like a lot of my horror

fiction, the novel is filled with weird shit. Like, a lot of it. I don’t

really label my horror in any specific ways, although readers, editors, and

reviewers have called it surreal horror, nightmare horror, weird horror,

and dark fantasy. And several of my short stories have appeared in

volumes of Year’s Best Hardcore Horror. Any of these labels is fine with

me, but I just think of my fiction as being my horror, fiction where the

psychological states of characters are mirrored in the outer world – sometimes

figuratively, sometimes quite literally. When I write this kind of horror, I

walk a fine line between explaining exactly what is happening and making it

seem plausible and allowing the images and concepts to speak for themselves

without much, if any explanation. Not every reader or editor likes my approach

to horror, but it’s worked pretty well for me over the last twenty-five years.

But it first appeared in my work about thirty-three years ago, in a story that

wasn’t horror at all.

I was an undergrad in college –

we’re talking mid-eighties here – I wrote a short story whose title escapes me

now. I have a vague memory of calling it “The Clearwater Monster,” but it could

just as easily have been titled something else. But I certainly remember the

story’s plot. It concerned two young boys who live near Lake Clearwater. One of

the boys has a fanciful imagination (I wonder where I got that idea) and

he likes to make up stories about a monster living in the lake and pretend that

there really is one. The imaginative boy drowns in the lake one day, and his

friend grieves. Years later, the friend – now an adult – returns to Lake

Clearwater for the first time since the imaginative boy died so many years ago.

The friend looks out upon the lake and is amazed and delighted to see a lake

monster, just like the one the imaginative boy described, swimming in the

water. He believes the monster is a manifestation of the boy’s spirit, who’s

made his stories become reality and who’s appeared to say a last farewell to

his old friend.

I showed this story to a guy I

worked with at the university writing center. We’ll call him Bob (because that

was his name). Bob read the story and gave me two pieces of feedback. One was

that I should specify where the lake was located. I hadn’t done this because I

wanted to create an almost fairy-tale sense that Clearwater could be any lake,

anywhere. “But you have to say where the lake is” Bob told me. “You’re an

American writer and all American writers are regionalists.” (And that, boys and

girls, is why you shouldn’t take Lit majors too seriously.)

The second bit of feedback focused

on the story’s ending, where the grown-up friend sees the lake monster swimming

by, as if purposefully putting on a show for him.

“It doesn’t make sense,” Bob said.

I explained my concept to him and

said that I didn’t want to overexplain it in the story because I felt doing so

would rob the final image – and the character’s emotional reaction to it – of

its impact. Bob insisted that the ending needed to be clearer, and since the

story was an experiment for me, I figured I’d try to do what Bob suggested and

see how it turned out. Giving Lake Clearwater a specific location was easy. I

lived – and still live – in Southwestern Ohio, so that became my lake’s home.

But as far as explaining the ending, everything I tried only made the story

worse. A lot worse. Instead of depicting a moment of magic in a person’s

life, a brief instant when he felt connected to his childhood friend once more,

the ending became bogged down with authorial narrative, and the more concrete

reasons I provided for the lake monster’s manifestation, the less magical the

image seemed. Eventually, I said to hell with it and gave up on the story

entirely. My creative instincts told me that my original approach was the right

one, but the rational part of my mind decided Bob was right, my instincts

sucked, and I moved on to other stories.

Bob’s feedback wasn’t the only

reason I abandoned the story. I’d read a ton of how-to-write books back then.

(This was long before the current wave of self-publishing, when only

professional authors wrote writing guides.)

So many of the books and articles I’d read advised beginning writers to

always be specific, never vague, and they advised writers to avoid such

literary tricks as leaving a story ending up to the reader to decide. They also

warned that purposefully making a story too abstract didn’t make you brilliant.

It meant you were an artistic poseur.

But as I kept writing, my urge to

write these kind of abstract, imagistic stories grew, and from time to time,

I’d give it another try. But when I did, I always made sure to offer at least

some explanation/justification for the story’s central image. A couple of these

stories sold to small-press magazines, back when the small press was really

small, but most didn’t sell at all.

And then one day when I was

twenty-nine, I decided to submit a story to a pro-level horror anthology called

Young Blood. The concept behind the anthology was that all the stories

in it had to have been written before the author’s thirtieth birthday. I wrote

a story about a monster tree called ‘Yggdrasil” that was quickly rejected. Then

I wrote a story called “Mr. Punch.” I’ve talked about writing this story a

number of times over the years – in interviews, and in past entries in this

blog. “Mr. Punch” was a total trust-my-instincts story, and when I received

feedback from friends that the ending needed to be explained more clearly, I

didn’t listen. I submitted “Mr. Punch,” the editor bought it, and it became my

first professional sale. Later, Ellen Datlow selected it as one of her honorary

mentions in The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror.

I continued writing and selling

such stories, ones that – as a colleague at the college where I teach once told

me – center on the “logic of the image.” Eventually, I tried to write this kind

of story at novel length. The result was The Harmony Society, which was

followed by my first Leisure Books release Like Death. (You can buy more

recent edition of these books in both print and ebook versions – hint, hint.)

Today, thirty-something years after writing about the Lake Clearwater Monster,

this is the type of horror fiction I’m known for, stories that have garnered awards

and appeared in various Year’s Best anthologies. Even so, I still occasionally

have editors ask me to explain my stories’ central concepts a bit more.

Sometimes I make changes, sometimes I don’t. It depends on whether I think a

clearer explanation will make a story better.

I can write stories that are clear

and easy to understand. I do it all the time when I write my urban fantasy or

tie-in novels. But there are very specific reasons why I think overexplaining

can be death for a horror story. (See what I did there?) Let me tell you why.

JOURNEY INTO THE

UNKNOWN

“The oldest and strongest emotion

of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the

unknown.” – H.P. Lovecraft

If you’re a horror writer, you’ve

likely seen this quote a jillion times before. The word unknown is key

here. Vampires ceased being scary as fictional characters long ago. They’re too

known. Not only do readers – especially rabid horror fans – know

everything about basic vampire lore, they’ve been exposed to images of vampires

in media since they were kids. When it comes to horror, overexplaining and

overfamiliarity have killed vampires (and werewolves and ghosts and . . .) with

more finality than sunlight and wooden stakes ever could. This is why vampires

relocated to urban fantasy and romance. Vampires are now primarily adventure

and romance characters. They aren’t Monsters with a capital M. By not overexplaining

a supernatural entity in a story – perhaps not even naming it – you keep readers

guessing, keep them uncertain, make them uncomfortable, make your story not safe

. . . Do these things, and you’re harnessing the power of the Unknown.

EXPLANATIONS –

ESPECIALLY DETAILED ONES – AREN’T REALISTIC

I know this sounds

counterintuitive, but hear me out. Imagine yourself as a character in a horror

story. You’re driving down a country road in the middle of the night, and you

see a full moon in the sky. You find this strange because you could’ve sworn a

full moon isn’t due for a couple more weeks. You peer at this unexpected moon

through your windshield, only to see its lid rise upward, revealing a single,

horrible gigantic eye gazing down at you. Do you really think you’d ever be

able to understand what the fuck was happening? That you could pull over to the

side of the road, park, grab your phone and do a Google search for “big-ass

moon eye” and a web page would pop up telling you exactly what the monstrous

eye is and precisely what to do to defeat it? Fuck, no! In real life, shit

happens all the time, and we hardly ever know for certain why it happens the

way it happens. We just have to try to deal with it the best we can.

The movie Sinister is a

great example of unnecessary and story-damaging overexplaining.

The monstrous fiend in the film is

called Mr. Boogie (as in Boogeyman, of course), and the shit that he causes to

happen is creepy as hell – until our hero consults a college professor who

explains that Mr. Boogie is really an ancient god called Bagul who collected

the souls of human children a thousand years ago.

Yawn.

Mr. Boogie was scary when he was a thing,

a creature of unknown abilities and motivations, who might not have any

motivation, at least none mere humans could ever understand. But Bagul? He’s

just a fifth-rate god in some obscure mythology text. What could be more dull?

(My guess is that Bagul shit was added at the direction of some dumbass studio

executive.)

MYSTERIOUS WAYS

Overexplaining kills any sense of

mystery in a story. There’s mystery in the Xenomorph in Alien. Not so

much in the sequel Aliens. In that movie, the Xenomorphs are more

numerous, easier to kill (at least as individuals), and their capabilities and

life cycle are much better understood by Ripley (though not completely). The

Xenomorph in Alien is a monster. The Xenomorphs in Aliens and

every other sequel are basically animals. You could replace them with a pack of

hyper-aggressive wolves and get pretty much the same story.

Alien: What is this

thing? Where did it come from? What does it want? What can it do? How does it

hunt? Reproduce? What can it do to me? How can I kill it?

Aliens: “Look, Xenomorphs!” Colonial Marines fire a shitload of bullets at

Xenos, tearing them to shreds.

Now I

love Aliens, and

while I think of it as an action-adventure movie with monsters, I don’t consider

it horror. Horror-adjacent at best.

Want an

example of a fantastic horror story that is drenched in mystery and the

unknown? Read Jack Ketchum’s “The Box.” You can also watch a great film

adaptation of the story as one part of the anthology film XX.

BUT SOMETIMES A LITTLE DOESN’T HURT

Sometimes

readers (and viewers) don’t respond well to stories that are only metaphor, so

giving them some explanation can help. It’s like Mary Poppins’ spoonful of sugar – it helps

the medicine go down. After I saw Darren Aronofsky’s Mother in the theater,

I had to hit the restroom. The guy using the urinal next to me asked if I’d

just seen the movie and if so, did I know what it was about? I told him what I

thought, he told me his theory, and then when were finished and our hands were

washed, he went into the hallway to look for other people who’d seen the movie

to find out what they thought it meant. While it was weird to have a discussion

with a stranger about a movie while we were both pissing, it was a good example

of an audience member who was almost desperate for a little more guidance in

how to view a story. So while I bitched about the Bagul stuff in Sinister earlier, a

line or two that at least hints at an explanation can go a long way to help

audiences who need something to hang onto when reading (or watching) a weird

story.

PURE IMAGINATION

I like

stories that stimulate my imagination. Explanations – especially unnecessarily

detailed ones – don’t feed my imagination. On the contrary, they starve it. They

keep me outside a story, when as an audience member, I want to be inside, interacting

with it intellectually and emotionally. Remember our old friend Mr. Boogie? For

most of Sinister, he was a mysterious, malign, inhuman presence, and this invited me to

try to imagine what the hell he might be, what he could do, and what he wanted.

But when I was told that he was just another pagan god, there was nothing left

for my imagination to work with. The script told me what the story was instead of allowing

me to help make the story. People attempt to define the difference between simplistic

fiction meant solely for mindless entertainment and stories that strive to

achieve more artistic goals. I’d say that inviting the audience to collaborate

in the creation of the story by allowing room for their imaginations to

interact with the text (or film) instead of merely spoonfeeding them

everything, is a pretty damn good definition.

There’s

nothing wrong with stories that are designed primarily to be fun. I’ve written

two creature-feature novels for Severed Press – The

Teeth of the Sea and Blood Island – and I created them solely to be enjoyable pulp adventure-horror. There’s

no great mystery to them, no strange imagery or ideas dredged up from my

subconscious, nothing but monsters chomping on people and people trying to

escape being chomped. But these books are the kind of thing readers read once

and then forget about. These stories don’t have any impact on readers, don’t

make them think or feel, and – most importantly to me -- they don’t stimulate readers’

imaginations in any meaningful way. They’re the simplest kind of horror, Goosebumps for adults.

They’re fun, but that’s all they are.

CONCLUSION

If you

want to write more challenging horror stories – stories which I think get

closer to the dark heart of what horror is instead of merely using horror

tropes to create simple entertainment – try playing around with how much, or

how little, you explain the weirdness in your stories and see what happens. Who

knows? You’ll at least add to your toolbox of narrative techniques for writing

horror, and you might just find a brand-new writer’s voice for yourself as well.

DEPARTMENT OF SHAMELESS SELF-PROMOTION

They Kill

As I

said earlier, They Kill has just been released, and is available simultaneously

in hardback, paperback, ebook, and audio. Advance reviews have been good! Here’s

one of my favorite review quotes:

“This is

gory, unsettling and definitely strange and I loved every minute. It’s what a

horror story should be and has reignited my love for the genre. Brilliant.” –

The Bookwormery

Can’t beat

that for a blurb, can you?

Here’s a

synopsis:

What are

you willing to do, what are you willing to become, to save someone you love?

Sierra

Sowell’s dead brother Jeffrey is resurrected by a mysterious man known only as

Corliss. Corliss also transforms four people in Sierra’s life into inhuman

monsters determined to kill her. Sierra and Jeffrey’s boyfriend Marc work to

discover the reason for her brother’s return to life while struggling to

survive attacks by this monstrous quartet.

Corliss

gives Sierra a chance to make Jeffrey’s resurrection permanent – if she makes a

dreadful bargain. Can she do what it will take to save her brother, no matter

how much blood is shed along the way?

Audio: Available

soon.

Writing in the Dark – the Book!

I’m

thrilled to have recently signed a contract with the good folks at Raw Dog

Screaming Press to write a horror-writing guide named after this blog: Writing in the Dark. I’ll

post information about release dates, etc., as it becomes available. For now,

you can find the official announcement about the book here: http://rawdogscreaming.com/book-deal-tim-waggoners-horror-writing-guide/

Prehistoric Anthology

I

mentioned earlier that I’ve written a couple monsters-chomping-people books for

Severed Press. I’ve also written a story for their anthology Prehistoric, which presents

stories about dinosaurs eating people. My story, “Closure,” is actually a

reimaging of a story I wrote for one of my college creative writing classes

when I was an undergrad over thirty years ago. I thought it would be cool to

see what I could do with the idea now, and “Closure” is the result. Check it

out!

Trade paperback:

https://www.amazon.com/PREHISTORIC-Dinosaur-Anthology-Hunter-Shea/dp/1925840875/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=&sr=

Alien: Prototype

My Alien

novel for Titan Books, Alien: Prototype, was recently approved by Fox Studios, so it’s good to go! It’ll be

out in October, and it’s also a fun monster-eating-people novel – but in SPACE!

Why should you read it? One word: Necromorph. (Yeah, I got to invent my own

alien species!) It’s available for preorder now.

Writing in the Dark Newsletter

Besides

this blog, I also have a newsletter you can subscribe to. I send issues out a

bit more frequently than I post here, and while the announcements about my current

and upcoming projects are mostly the same, I include writing and publishing

articles that are different than what you can read in my blog. The current

newsletter has an article on “The Rule of Twelve.” If you want to know what

that is, subscribe! You can do so by following this link at my website:

Newsletter

link: http://timwaggoner.com/contact.htm

Excellent article, Tim. I agree entirely that a horror story or sci-fi story shouldn't have to explain everything. Let's leave some room for the imagination and room for debate.

ReplyDeleteFunny how I hear your voice reading this to me...that doesn't happen too often, even though I know lots of writers IRL! ;-)

ReplyDeleteBecause I write straight crime fiction (as in no horror, not just hetero...you know what I mean!), I *have* to explain some things more, but I like things left to the imagination too - as a writer or as a reader.