I’ve been writing

and teaching for a long time. Because of this, I get a lot of people who reach

out to me via email or social media asking for advice about this or that. I’m

always happy to help if I can, but one of the most common questions I get runs something

along these lines: “I’ve got a great idea for a Supernatural novel. Can you hook me up with an editor that I can

pitch it to?” The answer, no matter how gently I try to phrase it, boils down

to “No.” And even if I was able to hook these writers up with an editor, it

likely wouldn’t do any good. So I decided to write a blog entry about how

writing and publishing media tie-ins really works, if for no other reason than

the next time somebody asks me how to do it, I can provide them a link to this

entry and say, “Read this.”

First, a little

about my background writing tie-ins. I’ve published over forty novels. Twenty

of them have been tie-ins. I’ve also written a number of short stories that are

tie-ins as well. I’ve written tie-ins based on roleplaying games, videogames,

movies, and TV shows. I’ve done original stories using licensed characters and

I’ve written novelizations of films. I’ve written articles on how to write

tie-ins for magazines like Writer’s

Digest. I’m also a member of the International Association of Media Tie-In

Writers. I’ve had work nominated for the association’s Scribe Awards numerous

times (still haven’t won yet, though), and several times I’ve served on juries

for the awards (never in the category I have work nominated in, of course). I

think it’s fair to say that I have some experience in this field, yes?

Here’s how tie-ins

work. A publisher decides that they would like to produce some tie-in novels

(or a tie-in anthology). They approach whoever holds the IP (intellectual

property) rights. For example, I just finished writing a novel set in the Alien

universe. Fox holds the rights to that property. The publisher says we would

like to produce five books based on your IP. The IP rights holder says okay, it

will cost you X amount of dollars. The publisher says cool beans. Now the

publisher has five books to find writers for. The publisher approaches writers

they’ve worked with before and says, “Pssst. Wanna write a book for us about

this IP?” and the writers say yes. (Or no if they’re busy with other projects

or if the advance offered isn’t enough for them or if they’re not interested in

the IP or uninterested in writing tie-ins in general.) If the publisher has

specific story requirements for the novels, they tell the writers. For example,

my Alien novel was set between two Alien comic series featuring a specific

character. So my story had to feature that character and take place between the

events of the two comic series. The writer comes up with some ideas and pitches

them to the editor. The editor picks one for the writer to develop into an

outline. Once the outline is ready, the editor sends it to the IP holder to

approve. The IP holder may say yes, no, or request some changes. If necessary,

the process continues until the IP holder approves an outline. The writer

writes the book, the editor reads it and suggests changes, the writer makes

revisions, the book goes to the IP holder for review, the IP holder makes

changes, and this process continues until both the IP holder and the editor are

happy. Then the book is finally approved. The writer will have to make more

changes during the copy-editing phase, but then the process is finally

finished, and eventually the book is released.

So given the

overall process above, here are some realities of tie-writing and publishing.

Publishers aren’t seeking tie-in pitches in general.

You can’t simply have

an idea for a tie-in and pitch it to a publisher. The publisher has to decide

they want to publish tie-ins, seek out a license, get it, schedule a certain

number of books, and then – and only then – are they open to pitches. You don’t

approach a publisher with a tie-in idea. They approach writers only when they

have tie-ins already scheduled and they need someone to write them.

Tie-Ins are not a market for new writers.

Publishers need

writers who have proven themselves in traditional publishing already. They’ve

written a number of books – usually in a genre or style similar to that of the

IP. They’ve proven they can write to deadline and produce a finished novel on

time. They’ve proven that they can work with editors and are open to revising

their fiction as part of the editorial process. In short, publishers of tie-ins

are looking for experienced professionals with a proven track record of

publication. And, of course, past experience writing tie-ins is a huge plus.

Simply put, writing tie-ins is not an entry-level job.

Publishers don’t care if you’re a fan of the IP.

If you’ve already

written novels based on that IP, that’s awesome. I’ve written a number of

novels based on the TV series Supernatural.

This makes it more likely publishers will ask me to write more of these.

Otherwise, publishers only care about what I said in the paragraph above.

Publishers won’t make an exception for you.

They can’t afford

to take a chance on someone without a proven track record when it comes to

tie-ins. Writers often have only a few months to write a tie-in novel. A few as

in three months. You might have been less time than that. You have to be able

to do the job and do it well under these time constraints. Publishers can’t

afford to gamble when it comes to this, hence their seeking out experienced

professionals.

It does matter if you’ve been traditionally published.

I am by no means

knocking indie writers here. But self-publishing isn’t the same as having

experience with the process of traditional publishing. Tie-ins are always

traditionally published. I suppose an indie writer could seek out an IP holder

and pay to acquire a license to produce a tie-in, but who has that kind of

money? Plus, IP holders are very careful about how their brands are portrayed

in other media. They trust publishers with proven track records. I doubt they’d

trust their IP with individual who isn’t affiliated with a traditional

publisher.

Experience writing and publishing short stories is

nice, but publishers want experienced novelists.

Short stories and

novels aren’t the same thing. When I say publishers want experienced writers, I

mean experienced novelists.

Small-Press credits are nice, but tie-ins aren’t

small-press projects.

I believe I’ve

only written one tie-in short story for a small-press publisher. Otherwise, all

my tie-in credits are for larger publishers. Tie-in publishers want writers

who’ve published with larger publishers like them. That said, depending on what

sort of novels you’ve written for small-press publishers (similar to the IP you

want to write for) and how well they were received (sales and reviews), they

might still make a good calling card when you approach a tie-in publisher.

So, given all of

the above, how can you gain the necessary experience if you want to write

tie-ins? Keep reading.

Write and publish original novels with (relatively)

large traditional publishers.

You need to establish

a track record in order to be considered for a tie-in writing gig. This is the

only way to do that. It’s possible to get a track record in other ways, such as

writing comics or videogames. That can show you have experience working with

other people’s IP’s. It doesn’t, however, show you can produce quality

novel-length fiction.

Get an agent.

Good agents

regularly check with publishers to see what they’re looking for. If a publisher

is looking for tie-in writers, agents can suggest one or more of their clients

for the gig. An agent can vouch for your skills and abilities if your

publication record is on the thin side, so you might not need as much

experience as if you were going it alone. As far as I know, no agents special

in tie-in fiction. It’s just one of the types of fiction they handle.

Network.

Networking will

not, repeat NOT, replace having experience and a track record. As I said in my

introduction, people ask me for advice on writing tie-ins all the time. Few, if

any, have landed any tie-in writing gigs afterward. That said, it doesn’t hurt

to follow tie-in writers and editors on social media to learn more about the

ins and outs of tie-in publishing. And if you do have significant publishing

credentials, then speaking to tie-in editors at conferences or asking advice

from tie-in writers might well be of benefit to you.

Continue working on becoming the very best writer you

can be.

Despite what some

people think, tie-in novels aren’t a lesser type of fiction produced by

second-rate writers. You have to be a damn good writer to land a tie-in gig. So

the more you do to make yourself a damn good writer, the greater chance you’ll

have.

So, does all this

mean that it’s impossible to break into writing tie-ins? Of course not. I did

it. My first tie-in novel, Dark Ages:

Gangrel, came out in 2004. Here’s a picture of an inscription Mike

Stackpole wrote in his 1996 Star Wars novel Rogue

Squadron.

I’d been trying to

break into tie-in writing for several years before I talked to Mike about it at

an Origins convention, and it still took eight years after that for my first

tie-in novel to appear. In the meantime, I kept writing and selling my original

fiction, honing my craft and gaining experience. And if you’re really serious

about writing tie-ins, that’s what you should do too.

DEPARTMENT OF SHAMELESS SELF-PROMOTION

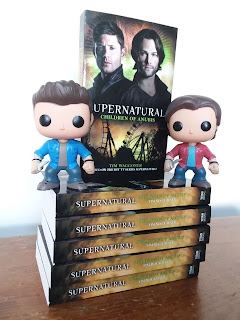

Speaking of tie-in

novels, my next Supernatural novel, Children

of Anubis, releases later this month. And my Alien novel, Protocol, is now available for preorder.

Linkage below.

Supernatural: Children of Anubis

Sam and Dean travel to Indiana, to investigate a

murder that could be the work of a werewolf. But they soon discover that

werewolves aren't the only things going bump in the night. The town is also

home to a pack of jakkals who worship the god Anubis: carrion-eating scavengers

who hate werewolves. With the help of Garth, the Winchester brothers must stop

the werewolf-jakkal turf war before it engulfs the town - and before the god

Anubis is awakened...

Alien: Protocol

When an industrial spy steals a Xenomorph egg, former

Colonial Marine Zula Hendricks must prevent an alien from killing everyone on

an isolated colony planet.

Corporate spy Tamar Prather steals a Xenomorph egg

from Weyland-Yutani, taking it to a lab facility run by Venture, a

Weyland-Yutani competitor. Former Colonial Marine Zula Hendricks--now allied

with the underground resistance--infiltrates Venture's security team. When a

human test subject is impregnated, the result is a Xenomorph that, unless it's

stopped, will kill every human being on the planet.

Release Date: Oct. 29. 2019